THE BANKS AND ISLANDS OF LIFE

My bones crack and snap now like Rice Crispies. I used to pour

from my bed ten years ago. That was ten years ago. Now my thumbs snap. I put

weight on my left hand and my shoulder attacks the forts. Now I’ve learned to

roll off my butt and swing my legs around. My knees will snap anyway, so I creep

like a steamroller. Why the thumbs crack, I don’t know. These snaps and cracks

infuriate me. I walk across the floor and my ankles wake up Melody. My ankles.

It’s ridiculous. I try to keep my ankles stiff, I try to control them, I try not

to bend them. What do they do? They snap and wake up Melody. But then she goes

back to sleep.

It’s dark.

I close the kids’ door like my dad used to close my door.

Before he went to work, Dad would close door after door to protect Macon and me

from light, from the toilet flushing, and from his cereal crunching. But really

(and I realize this now), the quiet protected his solitude.

My house used to be a schoolhouse in the 1800’s, so it tilts

like Boxcar Willie. The door comes toward me on its own and I have to stop it

before it clicks; it’s all timing. It’s a timing thing, really. I look at the

boys first, then leave them to their silence with the sweeping of the door.

Downstairs, I let my legs go. And yet all the snapping is

exhausted, which is once again both frustrating and infuriating.

I’m alone in the kitchen like my dad used to be. I pour my

corn flakes, only they’re not corn flakes now because something better today

made of wheat kernels keeps your bowels intact and contains a surprising amount

of trace minerals.

All I want to do is to sit in a chair in the living room and

not move. I want to just sit there and brace myself with one light on and stare

at this beautiful living room, not caring if I burn one calorie or ten. This

room is an arrangement, a happening, an event consisting of balance, plants,

good pictures, skill, sweat and plenty of thinking from atop a ladder, holding a

putty knife.

(So blended is this living room that no one would ever guess

about the ladder, putty knife and sweat, or that the room is one-hundred and

thirty-one years old. Melody worked hard on this room. I have never been able to

manage any kind of putty. But I did hold the ladder and the putty can,

worshipping Melody’s long hair from the trench of my valley.)

I compare enjoying the living room to reading a good book. No

one knows how it happened. No one knows what writers or putty people must do in

this world to make their projects rise from the dung hill.

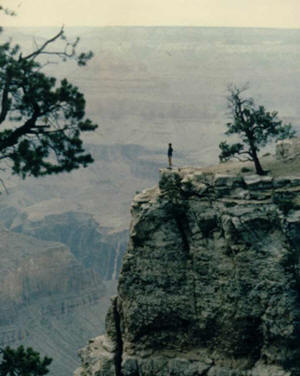

Above our sofa is a picture Melody took of me at the Grand

Canyon in 1984 during our trans-America bicycle trip. I had walked a good

distance around and away from Melody that day, then clambered down some rocks

onto a dangerous and stupid ledge that split the canyon. Melody exposed the film

during a rare opportunity.

In the picture, I’m a small black speck. Canyon in the morning

is behind me, with white sky climbing far up into the matting a foot over my

head. A tall tree climbs up the picture, just inside the left matting. The

matting is dark blue and so is the gorging foreground rock that offers me

deathward.

A scrubby tree invades the rock and leans toward the

risk-taker. The trunk of this tree continues in a dark way, cracking from this

rock. It makes a beautiful arc that shouldn’t be there. The picture is eleven

inches wide and fourteen inches tall. Something happened at the picture: there

are perfect lines and arcs. More lines and arcs appear with scrutiny. There are

lines that meet other lines, that meet other arcs, that meet the leaning tree,

that meet the openings that meet the leaves in the sky.

If morning were what I wanted it to be, dead objects would

live. Chairs in the room would walk, their springs would talk. Foam would

breathe. Furniture would clear its throat while the clock would at last be the

undominant sound.

People in books would come alive as well. My friends and

comrades in the volumes would rustle alive. Stage hands would hammer scenes into

scaffolds and everyone would cough. Then there would be boots and dainty shoes

shuffling toward the next scene. Just before the rising of the curtain,

everything would be quiet.

I want to read books, for myself. But I can’t do that because

I’m a husband and a father. Where does the spare time come from? The humidifier

bucket needs dumped two times a day. Bills need paid and the boys discovered the

ocean in a brown seashell while I was at work. The Spooky Old Tree (from the

book club) has also arrived, from the postman. So I think, a) if I dump the

bucket it will be done, b) if I tell the boys about the ocean they will want to

go with me there and c) if I read The Spooky Old Tree to them fourteen times,

they will love me forever.

In the morning, we are on the wall. I will stare and stare at

the family portrait. Maybe I will speak to it.

We may not always be smiling like this. I know that’s a

terrible thought, but I think it. That’s why family portraits are so good.

Families in portraits smile even into the dark and void, when everyone is in

bed. In this way is there hope in family portraits.

We blend in the picture so well because of Melody and the way

she chose our clothes.

Melody is beautiful. Her hair is full and thick and long. I

remember the skirt she wore at the picture, and so do thousands of others. Arty

makes me cry if I look too long.

Aaron is the little one here. He is two here, Arty is four.

Aaron is at the bottom of the picture and is being brave for the yellow duck. He

wants to please this duck by being himself for it. He will get a toy after this

and will make me laugh with it. He makes me laugh now.

The thing about night and the last parts of night is that the

banks of the river fall back into mud. Shells return to the ocean ooze, and some

oceans even retreat to their faraway holes. The nighttime creatures of The

Spooky Old Tree leave or have left their pages for the scent of deep woods.

There is a good, deep river between these woods and caves.

It’s before the dawn, under the stars, protecting people of Earth from the banks

and islands of life.